Rainwater Collection and Use at the Bullitt Center

In natural systems there‘s no such thing as waste: what dies or is discarded in one place becomes food or shelter someplace else. The intent of the Living Building Challenge’s Water Petal is to redefine our thinking about “waste” and to realign how we use water. This Petal isn’t about doing less bad but about actually restoring the land’s relationship with the water cycle to something much closer to its pre-development condition, in this case, restorative to a natural Douglas Fir forest.

The collection, treatment, use, and disposal of water are demanding requirements of the Living Building Challenge. The goal is to harvest and purify rainwater to satisfy all the water needs of the building’s occupants, and to cleanse and return used water to the hydrological cycle in an undiminished condition. The design team at the Bullitt Center has engineered a system to do just that. For now, however, the building will be connected to Seattle’s water supply system to provide potable water for sinks, showers and fire safety systems. Once the State Department of Health and Seattle Public Utilities have given it the OK, the system is designed to convert to using treated rainwater harvested on the roof as the sole source for potable water.

The collection, treatment, use, and disposal of water are demanding requirements of the Living Building Challenge. The goal is to harvest and purify rainwater to satisfy all the water needs of the building’s occupants, and to cleanse and return used water to the hydrological cycle in an undiminished condition. The design team at the Bullitt Center has engineered a system to do just that. For now, however, the building will be connected to Seattle’s water supply system to provide potable water for sinks, showers and fire safety systems. Once the State Department of Health and Seattle Public Utilities have given it the OK, the system is designed to convert to using treated rainwater harvested on the roof as the sole source for potable water.

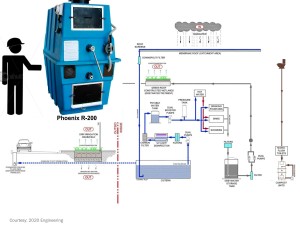

Early in the design process, 2020 Engineering out of Bellingham, Washington were brought onboard to study the feasibility of supplying all of the building’s water needs with rainwater collected on-site, then to treat used water and release this and unused rainwater to the ground and atmosphere, a unique requirement for an urban office building.

The two big issues to address in meeting the Net Zero Water requirement at the Bullitt Center were how to manage human waste (blackwater) and how to treat and return to the water cycle the greywater (water from sinks, showers, and floor drains). The solution for the first challenge is a composting system. The solution for the second challenge is to find enough space to store, treat and return greywater to the water cycle.

Rainwater landing on the PV array trickles through openings between panels onto the roof membrane underneath, is channeled to drains, screened and filtered, then carried by downspouts to a 56,000 gallon cistern in the basement. It enters at the base of the cistern and is withdrawn from a floating intake around 6” from the surface. From there it can travel through a number of different filtration and purification routes on its way to a 500-gallon potable water “day tank.” These various purification pathways will allow a number of different treatment options to be tested and documented. Initially this treated water will only supply the toilets, which use about a tablespoon of water to create a soap-foam transport medium for human “waste,” and for a few non-potable water hose bibs used for irrigation and cleaning. Once authorities have approved this system and the building is taken off the City water supply, the treated rainwater will be sent to the building’s sinks and showers.

Used water from sink, floor and shower drains (greywater) goes through screens to remove debris and hair and flows by gravity to a 400 gallon greywater storage tank in the basement. From here it is pumped up to the constructed wetland located on the roof over a portion of the second level on the north side of the building. One dose of greywater will be pumped up every two hours. Every half-hour the greywater will be re-circulated through the wetland so that each “dose” will pass through the aquatic system four times to maximize the uptake of nutrients into the plants. Some of the water will leave this wetland through evapotranspiration. The remaining treated, or “polished,” greywater will flow by gravity to a planted drip irrigation drain field built into the sidewalk on the west side of the building. Some of this water will return to the water cycle through evapotranspiration while the rest will be returned to the groundwater through an infiltration trench layered with pea gravel and soil.

While the water purification system will be fully in place to supply all the building’s needs with treated rainwater there remain two issues. Seattle Public Utilities (SPU) and the State Department of Health must permit this use, and the water will have to be chlorinated per federal regulations regarding surface water. Until these two items have been addressed, the Bullitt Center will rely on City water for potable uses. Because the Bullitt Center is within its service area, SPU must agree to allow a new public drinking water system within its jurisdiction. The State Department of Health requires that SPU agree to this before it will allow the Bullitt Center to use its own harvested and treated rainwater.

And there’s an additional challenge: chlorine is a Red List chemical under the Living Building Challenge, and therefore, it cannot be used in the building. However, according to federal regulations, rainwater is considered surface water (as opposed to ground water) and must be chlorinated before it can be used for potable purposes. Luckily the Living Building Challenge provides an exemption for any activity that is absolutely required by law. Under the federal Safe Drinking Water Act, chlorination is absolutely required for rain water used in a public water supply, and there is no administrative discretion.

By providing a fully functional system to treat, purify and return rainwater to the water cycle in an undiminished state, the Bullitt Center will help realign our relationship to water and “waste,” and inform future discussions on the laws governing water, sanitation, human and environmental health.